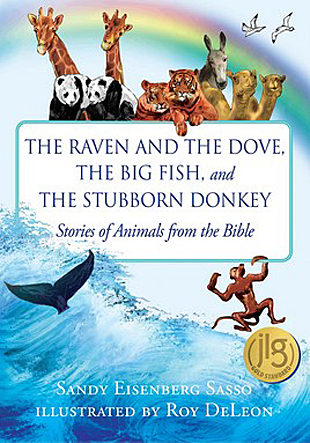

Both the author and illustrator of this book are well-known. Author Sandy Eisenberg Sasso has been publishing for children for thirty years; she’s the author of bestselling picture books such as God’s Paintbrush and In God’s Name. She was ordained in 1974, becoming only the second woman in the world to become a rabbi. And she has a Doctor of Ministry degree from Christian Theological Seminary. Her books have been used in many interfaith settings, and she’s spoken in several hundred synagogues and churches.

The illustrator, Roy DeLeon, is also a graphic designer, an experienced spiritual director, Benedictine oblate, and illustrator of The Pope’s Cat series of books for kids. He is also the author of a book we appreciated more than a decade ago, Praying with the Body.

This is their first project together. Sasso writes in her introduction, “Animals appear throughout the Bible from the very beginning…. They swim and fly, slither and climb all through the pages. The wolf lies down with the lamb, the ram arrives in the nick of time, and foxes run through vineyards. We read about them, but they have no voice of their own…. What if we were to allow the animals to speak, to tell us their feelings and their perspective about the world around them and the humans they encounter?”

The Bible that Sasso refers to, is the Hebrew scriptures, what Jews call the Tanakh, and Christians call the Old Testament. She chose three stories from those pages to retell here, from the perspective of the animals, birds, and fish: “The Raven and the Dove” retells the story of Noah’s Ark and the Flood; “The Big Fish” retells Jonah and the Whale; and “The Stubborn Donkey” recasts the least known of the three stories, what is often referred to as Balaam and the Donkey.

These stories are a form of “midrash”: interpretation of an ancient text that imaginatively “fills in gaps” in the original account, sometimes in the form of argument, retelling, or commentary.

“The Raven and the Dove” reveals the personalities of the birds who play a central role in the story of the flood that gave rise to Noah’s Ark and then receded enough for Noah to send out birds to investigate. The Raven, for instance, says, “Noah hates me because I am too loud, and I sometimes copy the way he talks,” explaining why the man in charge might be sending him out over the mysterious waters. Sasso also gives voice to Naamah, the name she gives to the person in the original text who is referred to simply and perhaps misogynistically as “Noah’s wife.” So, at the story’s end, when Noah calls out, “Thank God!”, Dove coos, “Thank Raven!” and Naamah adds, “Thank Dove!”

“The Big Fish” shows us what it might have felt like to take in that coward, Jonah. “I was just coming up for air when I opened my mouth and Jonah came gushing in,” reflects the big fish. “I was not at all pleased to swallow this bitter pill.” The big fish then takes Jonah on a life-altering, perspective-changing journey that helps to explain Jonah’s dramatic turnaround (see the excerpt accompanying this review).

Roy DeLeon’s illustrations are gorgeous throughout the book, drawn with both precision of detail and spirit of character and feeling — a combination that is difficult to achieve in picture book art.

We think Sasso’s version of the third story is even better than the original from chapter 22 of the Book of Numbers, the only time in the Bible, other than the serpent in the Garden of Eden, when an animal speaks to human beings. The donkey is clearly the hero here. And DeLeon’s illustration of a sword-bearing angel blocking the road ahead, explaining to Balaam that if it were not for his donkey’s interventions she would have killed Balaam — is beautiful.