There is something odd about giraffes, according to many Westerners who view them as bony and awkward creatures. Indigenous people, on the other hand, have great respect for them. They love the great variety in their fur patterns — no two are alike. They marvel at the fact that although giraffes have tongues that stretch 20 inches, they don't make many sounds and are silent most of the time.

Giraffes need only about three hours of sleep daily. They are the tallest creatures in the world. Their legs are six feet tall and yet they can bend down to drink from a pond. Shamans have surmised that when these creatures kneel, they are really meditating or praying. Some tribes perform a "Giraffe Dance" which is believed to be curative.

One Westerner who was intrigued by giraffes, beginning when she was a little girl and saw one at a zoo, was Anne Innis Dagg. In 1956 this Toronto-born zoologist traveled alone to South Africa to become the first researcher to study African animals in the wild — before Jane Goodall studied chimpanzees and Dian Fossey studied mountain gorillas. It took large reserves of courage for her to take this solo journey and carry on a year-long study of giraffe habits, diet, courtship patterns, and other behaviors.

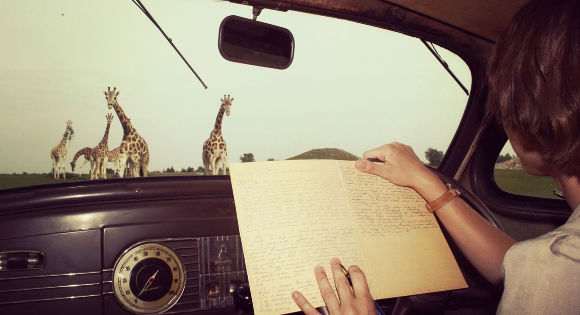

This wonder-filled biographical documentary uses old photographs, 16mm film footage, and voice-over readings from her letters to cover Dagg's time in Africa. She found lodging with a local landowner and went out into the bush daily to watch the herd of giraffes nearby.

Once she returned, she married and got a teaching job in Canada. But her bright and beautiful relationships with the giraffes was not mirrored by her experiences in academia. Due to the harsh and patriarchal attitudes at the university, she was denied tenure, a decision which kept her from getting the research funds needed to return to Africa for over 30 years.

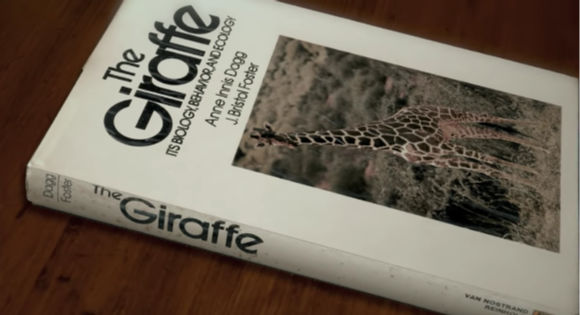

She did write the first definitive book on giraffes, however, and the documentary includes interviews with today's giraffe researchers, zoo-keepers, and wildlife advocates who talk about her tremendous influence on their work and the field.

The unfair treatment of Dagg is heart-breaking. So are the facts we learn about the pressures and problems faced by a declining population of wild giraffes today. But in the end, Dagg does get to return to Africa to see her favorite animals and to inspire younger scientists with her knowledge and enthusiasm.