"How does one kill fear, I wonder? How do you shoot a specter through the heart, slash of its spectral head, take it by its spectral throat?"

— Joseph Conrad

One would think there are enough things in everyday life to be afraid of — poverty and pain, crime and terrorism, disease and death. But the fact remains that horror films offer us a distinct pleasure — the experience of fear in a safe place. They give us a chance to deal with our paranoia about the outside world as well as the terrors which lurk within us. Horror movies play out before our eyes the antagonism of good vs. evil, light vs. dark, and instinct vs. reason. As we watch these contests, we feel our soul swing back and forth.

These are common themes in Stanley Kubrick's best movies — 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange: the hold imaginary worlds have upon us, the way certain individuals can be destroyed by their obsessions, and the slavery inherent in all of us. These themes are present again in The Shining, a screen adaptation of Stephen King's best-selling 1977 horror novel. As usual, Kubrick has paid great attention to the details of the cinematic craft — the soundtrack contains appropriately scary music from works by Bela Bartok, Gyorgy Ligeti, and Krysztof Penderecki; the camerawork by John Alcott is innovative; and the production design by Roy Walker is almost flawless. The screenplay is by Diane Johnson, an American novelist, and Kubrick.

"Almost as frightening as the idea of death — oh, just as frightening — is the realization that life can change on you, can darken like a rainy sky; wretchedness and dread can overtake the lightest heart, can take over the life ruled by love and harmony."

—form Diane Johnson's novel The Shadow Knows

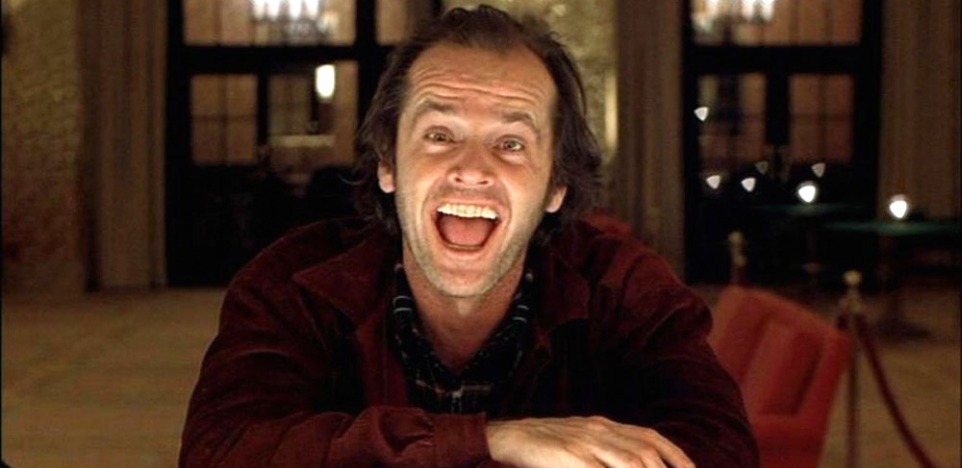

Jack Torrence (Jack Nicholson) is a writer and a tentatively reformed drunk. He's married to Wendy (Shelley Duvall), a nervous woman who is trying to hold together their wobbly marriage. They have one child, Danny (Danny Lloyd), who is gifted with "the shining" — precognition and mental telepathy. In the opening scenes of the film, Jack is interviewing for a job as the off-season caretaker of the Overlook Hotel in the Colorado mountains. Ullman (Barry Nelson), the hotel's manager, tells him that a previous caretaker went berserk due to the extreme loneliness and isolation of the place during the winter. He killed his wife, his two daughters, and himself. Meanwhile at home Danny has a vision of evil inhabiting the Overlook. His fears are confirmed later when he talks with Hallorann (Scatman Crothers), a cook at the hotel who also "shines." As the Torrences begin their stay alone in the massive resort, we wonder whether they will be done in by ghosts from the past or by their own demons.

"A film is — or should be — more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods or feelings. The theme, what's behind the emotion, the meaning, all that comes later. After you've walked out of the theatre, maybe the next day or a week later, maybe without ever actually realizing it, you somehow get what the filmmaker has been trying to tell you."

— Stanley Kubrick

Following the director's advice, we've allowed ourselves several days now to let The Shining simmer in our consciousness. As a ghost story, the film builds up a lot of tension but the releases are not very frightening or credible. One doesn't know if the ghoulish spirits from the hotel's checkered past are real presences — and a physical threat to Jack, Wendy, and Danny — or projections from their minds. Whether they are, they are neither terrifying nor menacing.

"You wouldn't ever hurt Mommy or me, would you?"

— Danny asks his father

The real fears in The Shining arise out of the mental state of the characters. What is the place doing to them and they to each other? Is marriage too ordinary, too everyday to become the motivation for murder? Or is it just the opposite? A recent book on violence in the American family noted that individuals run the greatest risk of assault, physical injury, and even murder not at the hands of strangers but by members of their own families. Is sanity that fragile? And do we all have a capacity for violence toward those we love? Jack Nicholson's intense portrait of a blocked writer's rage toward himself and his family is genuinely horrifying.

"The truth is always an abyss. One must — as in a swimming pool — dare to dive from the quivering springboard of trivial everyday experience and sink into the depths, in order to later rise again — laughing and fighting for breath — to the now doubly illuminated surface of things."

— Frank Kafka

The trend in present day horror films is to get the old adrenaline rushing by setting before our eyes grotesque killings and gruesome supernatural monsters. There is nothing in The Shining which approaches the brutality of scenes in Alien, Halloween, or Night of the Living Dead. The us-against-them formula is hackneyed, capable of bringing nothing more than nervous laughter from sensation seeking audiences. And the remnant of that focus in The Shining doesn't work. Perhaps the best thing about Kubrick's movie is that it goes half way toward bringing back Kafka's understanding of real horror as the evil which lies within.