By most accounts, the greatest teachings of Jesus come from one long text in the Christian New Testament called the “Sermon on the Mount.” This famous text can be found in the Gospel of Matthew, chapters 5, 6, and 7.

As Charles Moore explains in the introduction to his book, “The Sermon is masterfully poetical and also richly pictorial.” This is true. In fact, many of the lines from the Sermon on the Mount have become idiomatic in modern English, for example: “Blessed are the poor in spirit.” “You are the salt of the earth.” “Love your enemies.” “Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

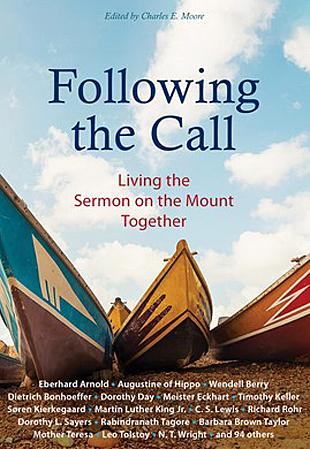

This fat book, generous with selections from more than 100 spiritual teachers past and present, ranges chronologically within Christianity from Cyprian of Carthage (early 3rd century) to Francis Chan (b. 1967) and Christena Cleveland (b. 1980). The denominational range is impressive too.

It includes many notable Catholics such as Francis of Assisi and Mother Teresa, Thomas Merton and Richard Rohr; Eastern Orthodox teachers include contemporary writer David Bentley Hart and the less known but saintly Nikolaj Velimirovic; notable Protestants such as contemporary writer Scot McKnight and great Black theologian Howard Thurman; Anglicans C.S. Lewis, Dorothy Sayers, and Barbara Brown Taylor; Evangelicals including the aforementioned Chan, as well as Philip Ryken and Elisabeth Elliot; and then the tough to categorize, such as psychiatrist M. Scott Peck and novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky. There are also contributors who are identified mostly as writers — poets or essayists — although we know they are Christian, such as William Blake and Wendell Berry. From other religious traditions, there are two: Rabindranath Tagore and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. It is interesting, to say the least, to read these teachers all in one place, on a series of topics that are so universal and important to the spiritual life, no matter what your religious tradition or path.

There are 52 chapters — too many to summarize — on topics such as “Blessedness,” “Poverty of Spirit,” “The Meek,” “Nonresistance,” “Perfect Love,” and “False Prophets.” A discussion guide at the back offers questions and prompts for each chapter, plus additional reading suggestions from the Christian Bible, designed, as the editor puts it, “to help readers live out the implications of Jesus’ teachings. How do we need to change?”

Here are a couple of examples. First, chapter 23, “Love of Enemy,” begins with the passage from the Sermon on the Mount in which Jesus says, “You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.” This is then followed by a long teaching from Martin Luther King, Jr. that includes these words:

“In the final analysis, love is not this sentimental something that we talk about. It’s not merely an emotional something. Love is creative, understanding goodwill for all men. It is the refusal to defeat any individual. When you rise to the level of love, of its great beauty and power, you seek only to defeat evil systems. Individuals who happen to be caught up in that system, you love, but you seek to defeat the system.”

Second, Chapter 14, “The Law,” begins with the passage from the Sermon where Jesus says, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.” Barbara Brown Taylor is the first to respond to this, and she says: “I am so sorry to tell you this, but Jesus was just not a very good Protestant. He was a Jew, for whom good works were not optional. He was the loving son of the Light-Giver who gave the law, and he expected those who followed him to follow it too…. God expects us to step up. Righteousness is a good thing…. Knowing God’s word is no substitute for doing it. Good works count.”