This book aims to resurrect and reimagine Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s interfaith vision of a “Beloved Community” in the United States. This vision aims to transform our neighborhoods, cities, and country.

Author Adam Russell Taylor is a husband and father, graduate of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, president of Sojourners — an ecumenical Christian organization that works to advance justice and peace — and a pastor at the Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia. He writes with additional authority about Dr. King, since Taylor is also a Black man in America.

Acknowledging and embracing the interrelatedness of life is essential to making the Beloved Community come to pass. “All [people] are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny,” Dr. King said. The Beloved Community, which King explained many times in his years of activism and ministry, is a land where all people are cared for and made safe from hatred, fear, and poverty.

Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King observed, as quoted here in chapter 4: “The Beloved Community is a realistic vision of an achievable society, one in which problems and conflict exist, but are resolved peacefully and without bitterness.”

“Building the Beloved Community requires truth-telling and repentance about our past,” Taylor writes in the introduction. “Instead of inciting guilt and casting blame, the Beloved Community is built on a foundation that generates empathy and galvanizes a greater commitment to justice.”

These themes run throughout all of Taylor’s chapters.

Chapter 11 looks at “Ubuntu Interdependence” and the teaching and example of Archbishop Desmond Tutu for how South African lessons may be extended into new practices of economic growth, promotion of the public good, and prosperity for all people in the U.S. Billionaires, advocates for the poor, and Republicans and Democrats are brought together in Taylor’s discussions to bear on these issues. The result seems to be that meaningful change is truly possible and feasible.

Myths have to be unmasked, and Taylor does this well, too, always with evidence. Polarization of communities must be overcome, and Taylor both quantifies the divisions and works to give practical hope for their resolutions.

If and when these sorts of real changes are brought to bear in American life, Taylor imagines that it is possible to then “redeem” patriotism from the clutches of destructive nationalism.

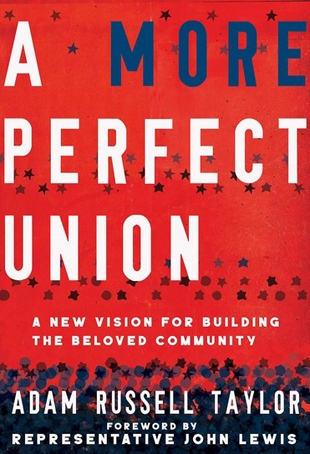

Just before he died, Representative John Lewis wrote in his foreword to Taylor’s book, “I still believe in the power of the Beloved Community vision to ultimately transform our nation into a more perfect union. I still believe that we will create the Beloved Community, we will redeem the soul of America. I still believe we shall overcome.”

Throughout his work, Taylor marshals the support of many of our most active and articulate workers for justice across the religious traditions, such as Rev. William Barber II, founder of the Moral Mondays movement; Princeton professor Dr. Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.; Joseph Kunkel, director of MASS Design Group’s Sustainable Native Communities Design Lab; Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, of the Poor People’s Campaign; Pope Francis, author of Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home; Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, founders of Black Lives Matter; Eboo Patel, founder and president of Interfaith Youth Core; and the recently deceased Dr. Paul Farmer, co-founder of Partners in Health.

Taylor reminds us — with data, the advice of experts, and an abundance of personal experience — how transformation is possible. His language is accessible, and he often reminds us of the role of personal responsibility, as when he says in a late chapter on environmental stewardship: “Our daily stewardship decisions are important. Even more important is how we use our voices and power as citizens, consumers, and voters. We must transform the politics of denial, delay, and incrementalism into a politics of urgent, audacious, and transformational action.”