At one point, late in this warm and engaging memoir, the author reflects that through spinning and knitting “Restrictions do move aside, pathways clear, and, for the moment, anyway, everyday life begins to return.” It is good therapy for her. But it is also more than that.

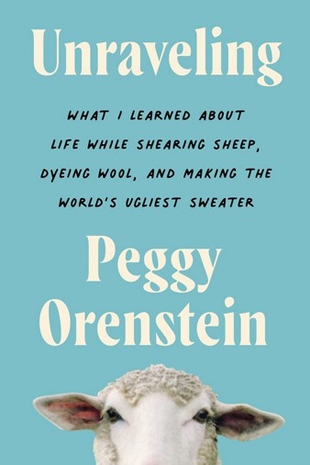

Spinning, dyeing, and knitting wool have become a way of deepening relationships with friends and aging parents, for Peggy Orenstein, a New York Times bestselling author of other books of a different sort (about sexuality and gender, mostly). For her, working with wool is also a path to political activism. Unraveling is not at all a “spirituality of knitting”; such books exist, and this is not one of them. Instead, Orenstein offers what she explains as the ideal craft for realizing “now is all we have.”

She lives in California, north of San Francisco in Sonoma County, and writes about her friends, experiences, and familiar places in ways that feel relatable to any reader where they live. She is also Jewish and writes occasionally about that.

And she writes about sheep, sheep farming and shearing, turning wool into yarn, and knitting craft. In many ways, this book will cause people to consider where their clothes come from, just as Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma caused many to understand how the food they eat made it to their table. Orenstein writes, “If I care about the ethics of what I put into my body, I have no choice but to care equally about what I put onto it.”

Most of all, we came away from her memoir with an understanding of how spinning and knitting relate to slowing down time. To working with one’s hands. Toward disrupting the fast and often damaging ways of capitalism (she refers to Mahatma Gandhi’s teachings about spinning cloth, in this regard). For becoming better connected to the natural world. And we realized, these are all spiritual practices.