Australian film director Ray Lawrence's 2001 film Lantana is a richly nuanced psychological drama that circles around the complicated subject of love offering ample insights into the sources of emotional illiteracy, especially in men. Jindabyne is based on the story "So Much Water So Close to Home" by American writer Raymond Carter, which was also a section in Robert Altman's Short Cuts. The well-done screenplay by Ray Lawrence and Beatrix Christian vividly conveys the moral divisiveness that swirls through a rural community when some men chose the pursuit of their own pleasure over adult responsibility. Jindabyne dares to take a long and hard look at how the ethical decisions we make affect many people outside our inner circle of family and friends.

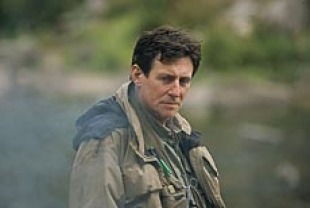

The town of Jindabyne is a peculiar place that was relocated when it was covered by rising waters due to the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Plan. The land that was submerged also was the sacred place of local aboriginals. Stewart (Gabriel Byrne) runs a gas station and is married to Claire (Laura Linney), a woman who years ago abandoned him and their young son for 18 months. Ever since then, their marriage has been on shaky ground. His Catholic mother Vanessa (Betty Lucas) is still interfering in their relationship.

Stewart's best friends are Carl (John Howard) and Rocco (Stelios Yiakmis). Carl is married to Jude (Deborra-lee Furness); they are raising their troubled grand-daughter Caylin-Calandria (Eva Lazzaro), whose mother died recently. Rocco (Stelios Yiakmis) has surprised his friends by dating Carmel (Leah Purcell), an aboriginal school teacher. Another male in the community is Billy (Simon Stone), who works for Stewart and is in love with Elissa (Alice Garner).

Stewart and his friends love fishing and decide to take Billy along with them on a trip to a river in the mountains where trout are plenteous. They take special pride in the fact that women are not allowed on the journey, and so are upset with Billy when he tries to communicate with his girlfriend by phone. But the sheer magic of being in the wilderness without a care in the world is shattered when Stewart comes upon the nearly nude body of a dead aboriginal girl floating in the water. They do not know what to do. Instead of reporting the tragedy to the police, they decide to tether the body to a tree near the water and continue with their fishing excursion for another day. When they return, they find that their wives and other members of the community cannot believe their callous and insensitive treatment of the aboriginal girl. Would they have done the same thing if it were a little white boy or girl?

The relatives of the murdered girl are so enraged that they commit various acts of vandalism against the fishermen's property. Claire is astonished by her husband's silence about what happened in the mountains and ashamed of his actions. She single-handedly tries to make contact with the dead girl's family and even goes so far as to raise some money to give to them to help allay funeral expenses. It is fascinating to watch her compassion and yearning for reconciliation while the men continue to act as if they did nothing wrong since the woman was already dead and there was nothing they could do for her.

Ray Lawrence's sobering and serious movies reach into our hearts thanks to the respect he has for the mysteries of love, loss, community, and reconciliation. The town is a haunted place, and each of the main characters is hobbled by some burden that makes his or her personal journey more difficult. The closing scenes show how ritual can draw people together even when they are torn apart by hatred, anger, and grief. We can choose to move beyond the haunted parts of our lives and begin anew.