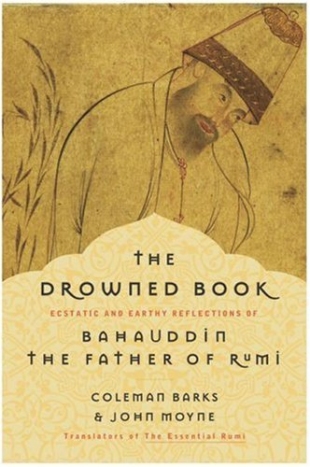

Bahauddin Valad (1152-1231) was the father of the great mystical poet and seer Rumi. He was known in Konya as "King of Learned Men, Sultan of Mystical Knowing." In this first ever translation of important passages in the Maarif, his spiritual notebook, the inimitable Coleman Barks and Persian scholar John Moyne take us on enthralling adventure into the presence of God in this great soul's life. They describe this volume as a "mystical compost heap" with its fecund collection of visionary insights, questions and responses, conversations with God, commentary on passages from the Qur'an, stories, bits of poetry, sudden revelations, medical advice, gardening hints, dream records, jokes, erotic episodes, and speculations of all kinds. This much admired and respected Persian spiritual teacher has much to say about the spiritual practices of yearning, grace, mystery, attention, gratitude, joy, and imagination. As Barks and Moyne put it, "Bahauddin stands before us as a multidimensional traffic junction, not as poet, though a maker of wild paragraphs, not as a coherent theologian, although a brilliant igniter of images in the cave of the unknowable."

Rumi's father inspired him to emphasize yearning as a central pathway to the Holy One. This inventive book is filled with passages where Bahauddin prays for his desires to increase and deepen. There is no separation of body and soul in his writings — the intention is to live every moment in the divine. "I go to your door to pass the time. We walk out together. In five-times prayer I ask you to accept this homage, and please, to keep my body vibrant with new varieties of favors and the familiar pleasures too." He advances further along this line when he writes:

"I notice that every part of my body and my awareness is ready to receive each of these cravings. I have more of them than most because I ask for more. They come as gifts. When my sexual desire gets satisfied, my entire body feels pleased and peaceful. And looking at a beautiful woman delights me greatly. Why are people so agitated about these things, when all they have to do is live in the love of the presence? I am faithful to that, and the way of pleasure and satisfaction has opened to me. There are many different ways. Some have nothing in common with others. Mine is unique to me, and I enjoy it tremendously. The world I see is even more beautiful and pleasurable than the one we accept in common. Many people want to be like me, but I have no desire to be like them. Which proves that I have been given a more delicious life than the one they live. God knows best."

No wonder Barks and Moyne call Bahauddin "a juicy mystic." He is not a devotee of reason, which grows wan in the face of divine revelation through the diverse beauties and bounties of the created world. Rumi's father believes that the path of the heart is not easily described with words or concepts: "When I am asked about the nature of love, I say nothing. I point to those thousands of surrendered, prophetic souls. Talking about love obscures the essence. Whatever transpires between lovers can never be said. It's a living mystery. Taste and feel it without verbal exchange. Relish it in your soul, your heart, your personality. Taste the taste with your entire body, and here in the tongue. But not by speaking." Another dimension of living with mystery is not planning for the future but always simply giving praise to God. He uses the image: "Give yourself in the way seeds get planted. Disappear in the ground, no trace, as a tree begins to grow with branches that reach their blind trust into the air. Great multiples grow from trusting."

Bahauddin has much to say about the role of friendship among Sufis and the relationship to the Friend. It is seen as the source of flourishing; doing inner work with those we trust is the means whereby we test our wings. Best of all, this idiosyncratic spiritual teacher salutes the presence of God as a grace that comes in both light and dark, troubles and pleasure, tears and laughter. "That presence can sometimes take the form of a disaster, a deepened awareness, or something more hidden. It may come when you are sitting quietly at home with your children and your wife, or in the devotion with which you do your work," he writes. He continues with this advice: "Remember to move within and live as close as you can to that, and if you feel yourself moving apart from it, don't go to others for companionship. A child cries until the mother comes. Be that demanding. Listen to music and song until your divine Friendship revives. Listen to those who achingly long for God. Noah was a prophet because he so constantly feared losing the closeness."

In another place, Bahauddin challenges us to be on constant alert for "porters of grace." This spiritual notebook contains a treasure trove of insights into the mystical path of the heart. Rumi's father saw himself as a wild-madman-lover, and he certainly passed on that legacy to his son. We will gladly return to this extraordinary Sufi commonplace book again and again to whet our appetite for yearning, mystery, and grace.